City of dreams

A Chinese eco-city

Mar 19th 2009 | DONGTAN From The Economist print edition

Still on the drawing-board

IDEAS about tackling China’s myriad environmental woes, from soil erosion to polluted waterways, tend to come in outsize packages—hardly surprising, given the scale of the damage. Bold environmental solutions are as appealing to policymakers as they are to engineers who want to put their stamp on the cities of tomorrow. One such project is Dongtan, a planned eco-city on an alluvial island near Shanghai. Designed by Arup, a British design firm, to house 500,000 people on a 8,600-hectare (21,250-acre) site, it was billed as a low-carbon alternative to urban sprawl and a blueprint for other eco-cities. But four years on, not a single green building has gone up on the site.

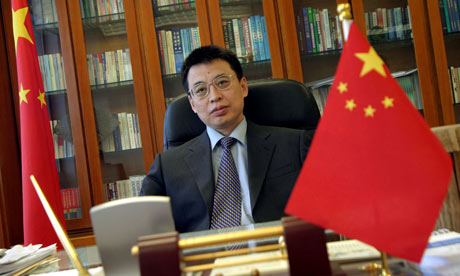

The reason lies not in the spluttering global economy but in the political corridors of Shanghai, the powerful city to which Chongming island belongs. A prime mover behind Dongtan was a former Shanghai Communist Party chief, Chen Liangyu, who steered the land into the hands of Shanghai Industrial Investment Corporation, or SIIC, a state-owned developer, and lent his prestige to the project. Then, in 2006, Mr Chen was sacked for property-related corruption. He was later convicted and is under house arrest. The way big land deals are done in Shanghai has been changed.

A noticeable loser is Dongtan. Arup’s original plan had 50,000 residents moving in by 2010, when Shanghai hosts the World Expo. That has now been quietly dropped. Arup’s Roger Wood says SIIC has opted to put construction on hold, pending further permits. He denies, however, that the project has been cancelled. On a recent visit to the site, your correspondent found an SIIC business centre and a shuttered hotel, neither of which appear in the master plan. Local residents say the hotel, outside the site proper, was a private villa owned by Mr Chen, who presumably enjoyed his excursions to Chongming.

A new bridge and tunnel spanning the estuary is already completed and will open to traffic later this year. That should boost land prices on Chongming, and may give SIIC a nudge to develop—or sell—the Dongtan site. It also raises the question, however, of what constitutes an eco-city. Arup had envisaged a compact, mostly car-free community. Residents would live and work in green research centres and other such industries, buy local produce and use renewable energy. The new road link, however, puts Shanghai within commuting distance. Locals also talk excitedly of future sales of holiday and retirement homes—hardly the original idea. Critics also point out that building an eco-city on farms near hugely important wetlands, which attract rare migrating birds (and birdwatchers), was always dubious. For its part, Arup said the wetlands would be protected by a buffer zone around the city.

A more obvious strategy might seem to be to rebuild a polluted industrial zone in China’s rustbelt and insist on smart design and energy efficiency. But China is urbanising so relentlessly that vast tracts of housing will have to be built somewhere. By 2030, the urban population is forecast to reach 1 billion, according to McKinsey Global Institute. Better to plan new, more efficient cities than allow car-dependent urban sprawl to eat up farmland around existing urban centres, goes the thinking. Better still, of course, to build them.