BEIJING: No country in history has emerged as a major industrial power without creating a legacy of environmental damage that can take decades and big dollops of public wealth to undo.

But just as the speed and scale of China's rise as an economic power have no clear parallel in history, so its pollution problem has shattered all precedents. Environmental degradation is now so severe, with such stark domestic and international repercussions, that pollution poses not only a major long-term burden on the Chinese public but also an acute political challenge to the ruling Communist Party. And it is not clear that China can rein in its own economic juggernaut.

Public health is reeling. Pollution has made cancer China's leading cause of death, the Ministry of Health says. Ambient air pollution alone is blamed for hundreds of thousands of deaths each year. Nearly 500 million people lack access to safe drinking water.

Chinese cities often seem wrapped in a toxic gray shroud. Only 1 percent of the country's 560 million city dwellers breathe air considered safe by the European Union. Beijing is frantically searching for a magic formula, a meteorological deus ex machina, to clear its skies for the 2008 Olympics.

Environmental woes that might be considered catastrophic in some countries can seem commonplace in China: industrial cities where people rarely see the sun; children killed or sickened by lead poisoning or other types of local pollution; a coastline so swamped by algal red tides that large sections of the ocean no longer sustain marine life.

China is choking on its own success. The economy is on a historic run, posting a succession of double-digit growth rates. But the growth derives, now more than at any time in the recent past, from a staggering expansion of heavy industry and urbanization that requires colossal inputs of energy, almost all from coal, the most readily available, and dirtiest, source.

"It is a very awkward situation for the country because our greatest achievement is also our biggest burden," says Wang Jinnan, one of China's leading environmental researchers. "There is pressure for change, but many people refuse to accept that we need a new approach so soon."

China's problem has become the world's problem. Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides spewed by China's coal-fired power plants fall as acid rain on Seoul, South Korea, and Tokyo. Much of the particulate pollution over Los Angeles originates in China, according to the Journal of Geophysical Research.

More pressing still, China has entered the most robust stage of its industrial revolution, even as much of the outside world has become preoccupied with global warming.

Experts once thought China might overtake the United States as the world's leading producer of greenhouse gases by 2010, possibly later. Now, the International Energy Agency has said China could become the emissions leader by the end of this year, and the Netherlands Environment Assessment Agency said China had already passed the milestone.

For the Communist Party, the political calculus is daunting. Reining in economic growth to alleviate pollution may seem logical, but the country's authoritarian system is addicted to fast growth. Delivering prosperity placates the public, provides spoils for well-connected officials and forestalls demands for political change. A major slowdown could incite social unrest, alienate business interests and threaten the party's rule.

But pollution poses its own threat. Officials blame fetid air and water for thousands of episodes of social unrest. Health care costs have climbed sharply. Severe water shortages could turn more farmland into desert. And the unconstrained expansion of energy-intensive industries creates greater dependence on imported oil and dirty coal, meaning that environmental problems get harder and more expensive to address the longer they are unresolved.

China's leaders recognize that they must change course. They are vowing to overhaul the growth-first philosophy of the Deng Xiaoping era and embrace a new model that allows for steady growth while protecting the environment. In his equivalent of a State of the Union address this year, Prime Minister Wen Jiabao made 48 references to "environment," "pollution" or "environmental protection."

The government has numerical targets for reducing emissions and conserving energy. Export subsidies for polluting industries have been phased out. Different campaigns have been started to close illegal coal mines and shutter some heavily polluting factories. Major initiatives are under way to develop clean energy sources like solar and wind power. And environmental regulation in Beijing, Shanghai and other leading cities has been tightened ahead of the 2008 Olympics.

Yet most of the government's targets for energy efficiency, as well as improving air and water quality, have gone unmet. And there are ample signs that the leadership is either unwilling or unable to make fundamental changes.

Land, water, electricity, oil and bank loans remain relatively inexpensive, even for heavy polluters. Beijing has declined to use the kind of tax policies and market-oriented incentives for conservation that have worked well in Japan and many European countries.

Provincial officials, who enjoy substantial autonomy, often ignore environmental edicts, helping to reopen mines or factories closed by central authorities. Over all, enforcement is often tinged with corruption. This spring, officials in Yunnan Province in southern China beautified Laoshou Mountain, which had been used as a quarry, by spraying green paint over acres of rock.

President Hu Jintao's most ambitious attempt to change the culture of fast-growth collapsed this year. The project, known as "Green GDP," was an effort to create an environmental yardstick for evaluating the performance of every official in China. It recalculated gross domestic product, or GDP, to reflect the cost of pollution.

But the early results were so sobering — in some provinces the pollution-adjusted growth rates were reduced almost to zero — that the project was banished to China's ivory tower this spring and stripped of official influence.

Chinese leaders argue that the outside world is a partner in degrading the country's environment. Chinese manufacturers that dump waste into rivers or pump smoke into the sky make the cheap products that fill stores in the United States and Europe. Often, these manufacturers subcontract for foreign companies — or are owned by them. In fact, foreign investment continues to rise as multinational corporations build more factories in China. Beijing also insists that it will accept no mandatory limits on its carbon dioxide emissions, which would almost certainly reduce its industrial growth. It argues that rich countries caused global warming and should find a way to solve it without impinging on China's development.

Indeed, Britain, the United States and Japan polluted their way to prosperity and worried about environmental damage only after their economies matured and their urban middle classes demanded blue skies and safe drinking water.

But China is more like a teenage smoker with emphysema. The costs of pollution have mounted well before it is ready to curtail economic development. But the price of business as usual — including the predicted effects of global warming on China itself — strikes many of its own experts and some senior officials as intolerably high.

"Typically, industrial countries deal with green problems when they are rich," said Ren Yong, a climate expert at the Center for Environment and Economy in Beijing. "We have to deal with them while we are still poor. There is no model for us to follow."

In the face of past challenges, the Communist Party has usually responded with sweeping edicts from Beijing. Some environmentalists say they hope the top leadership has now made pollution control such a high priority that lower level officials will have no choice but to go along, just as Deng Xiaoping once forced China's sluggish bureaucracy to fixate on growth.

But the environment may end up posing a different political challenge. A command-and-control political culture accustomed to issuing thundering directives is now under pressure, even from people in the governing party, to submit to oversight from the public, for which pollution has become a daily — and increasingly deadly — reality.

Perpetual Haze

During the three decades since Deng set China on a course toward market-style growth, rapid industrialization and urbanization have lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty and made the country the world's largest producer of consumer goods. But there is little question that growth came at the expense of the country's air, land and water, much of it already degraded by decades of Stalinist economic planning that emphasized the development of heavy industries in urban areas.

For air quality, a major culprit is coal, on which China relies for about two-thirds of its energy needs. It has abundant supplies of coal and already burns more of it than the United States, Europe and Japan combined. But even many of its newest coal-fired power plants and industrial furnaces operate inefficiently and use pollution controls considered inadequate in the West.

Expanding car ownership, heavy traffic and low-grade gasoline have made autos the leading source of air pollution in major Chinese cities. Only 1 percent of China's urban population of 560 million now breathes air considered safe by the European Union, according to a World Bank study of Chinese pollution published this year. One major pollutant contributing to China's bad air is particulate matter, which includes concentrations of fine dust, soot and aerosol particles less than 10 microns in diameter (known as PM 10).

The level of such particulates is measured in micrograms per cubic meter of air. The European Union stipulates that any reading above 40 micrograms is unsafe. The United States allows 50. In 2006, Beijing's average PM 10 level was 141, according to China's National Bureau of Statistics. Only Cairo, among world capitals, had worse air quality as measured by particulates, according to the World Bank.

Emissions of sulfur dioxide from coal and fuel oil, which can cause respiratory and cardiovascular diseases as well as acid rain, are increasing even faster than China's economic growth. In 2005, China became the leading source of sulfur dioxide pollution globally, the State Environmental Protection Administration, or SEPA, reported last year.

Other major air pollutants, including ozone, an important component of smog, and smaller particulate matter, called PM 2.5, emitted when gasoline is burned, are not widely monitored in China. Medical experts in China and in the West have argued that PM 2.5 causes more chronic diseases of the lung and heart than the more widely watched PM 10.

Perhaps an even more acute challenge is water. China has only one-fifth as much water per capita as the United States. But while southern China is relatively wet, the north, home to about half of China's population, is an immense, parched region that now threatens to become the world's biggest desert.

Farmers in the north once used shovels to dig their wells. Now, many aquifers have been so depleted that some wells in Beijing and Hebei must extend more than half a mile before they reach fresh water. Industry and agriculture use nearly all of the flow of the Yellow River, before it reaches the Bohai Sea.

In response, Chinese leaders have undertaken one of the most ambitious engineering projects in world history, a $60 billion network of canals, rivers and lakes to transport water from the flood-prone Yangtze River to the silt-choked Yellow River. But that effort, if successful, will still leave the north chronically thirsty.

This scarcity has not yet created a culture of conservation. Water remains inexpensive by global standards, and Chinese industry uses 4 to 10 times more water per unit of production than the average in industrialized nations, according to the World Bank.

In many parts of China, factories and farms dump waste into surface water with few repercussions. China's environmental monitors say that one-third of all river water, and vast sections of China's great lakes, the Tai, Chao and Dianchi, have water rated Grade V, the most degraded level, rendering it unfit for industrial or agricultural use.

Grim Statistics

The toll this pollution has taken on human health remains a delicate topic in China. The leadership has banned publication of data on the subject for fear of inciting social unrest, said scholars involved in the research. But the results of some research provide alarming evidence that the environment has become one of the biggest causes of death.

An internal, unpublicized report by the Chinese Academy of Environmental Planning in 2003 estimated that 300,000 people die each year from ambient air pollution, mostly of heart disease and lung cancer. An additional 110,000 deaths could be attributed to indoor air pollution caused by poorly ventilated coal and wood stoves or toxic fumes from shoddy construction materials, said a person involved in that study.

Another report, prepared in 2005 by Chinese environmental experts, estimated that annual premature deaths attributable to outdoor air pollution were likely to reach 380,000 in 2010 and 550,000 in 2020.

This spring, a World Bank study done with SEPA, the national environmental agency, concluded that outdoor air pollution was already causing 350,000 to 400,000 premature deaths a year. Indoor pollution contributed to the deaths of an additional 300,000 people, while 60,000 died from diarrhea, bladder and stomach cancer and other diseases that can be caused by water-borne pollution.

China's environmental agency insisted that the health statistics be removed from the published version of the report, citing the possible impact on "social stability," World Bank officials said.

But other international organizations with access to Chinese data have published similar results. For example, the World Health Organization found that China suffered more deaths from water-related pollutants and fewer from bad air, but agreed with the World Bank that the total death toll had reached 750,000 a year. In comparison, 4,700 people died last year in China's notoriously unsafe mines, and 89,000 people were killed in road accidents, the highest number of automobile-related deaths in the world. The Ministry of Health estimates that cigarette smoking takes a million Chinese lives each year.

Studies of Chinese environmental health mostly use statistical models developed in the United States and Europe and apply them to China, which has done little long-term research on the matter domestically. The results are more like plausible suppositions than conclusive findings.

But Chinese experts say that, if anything, the Western models probably understate the problems.

"China's pollution is worse, the density of its population is greater and people do not protect themselves as well," said Jin Yinlong, the director general of the Institute for Environmental Health and Related Product Safety in Beijing. "So the studies are not definitive. My assumption is that they will turn out to be conservative."

Growth Run Amok

As gloomy as China's pollution picture looks today, it is set to get significantly worse, because China has come to rely mainly on energy-intensive heavy industry and urbanization to fuel economic growth. In 2000, a team of economists and energy specialists at the Development Research Center, part of China's State Council, set out to gauge how much energy China would need over the ensuing 20 years to achieve the leadership's goal of quadrupling the size of the economy.

They based their projections on China's experience during the first 20 years of economic reform, from 1980 to 2000. In that period, China relied mainly on light industry and small-scale private enterprise to spur growth. It made big improvements in energy efficiency even as the economy expanded rapidly. Gross domestic product quadrupled, while energy use only doubled.

The team projected that such efficiency gains would probably continue. But the experts also offered what they called a worst-case situation in which the most energy-hungry parts of the economy grew faster and efficiency gains fell short.

That worst-case situation now looks wildly optimistic. Last year, China burned the energy equivalent of 2.7 billion tons of coal, three-quarters of what the experts had said would be the maximum required in 2020. To put it another way, China now seems likely to need as much energy in 2010 as it thought it would need in 2020 under the most pessimistic assumptions.

"No one really knew what was driving the economy, which is why the predictions were so wrong," said Yang Fuqiang, a former Chinese energy planner who is now the chief China representative of the Energy Foundation, an American group that supports energy-related research. "What I fear is that the trend is now basically irreversible."

The ravenous appetite for fossil fuels traces partly to an economic stimulus program in 1997. The leadership, worried that China's economy would fall into a steep recession as its East Asian neighbors had, provided generous state financing and tax incentives to support industrialization on a grand scale.

It worked well, possibly too well. In 1996, China and the United States each accounted for 13 percent of global steel production. By 2005, the United States share had dropped to 8 percent, while China's share had risen to 35 percent, according to a study by Daniel H. Rosen and Trevor Houser of China Strategic Advisory, a group that analyzes the Chinese economy.

Similarly, China now makes half of the world's cement and flat glass, and about a third of its aluminum. In 2006, China overtook Japan as the second-largest producer of cars and trucks after the United States.

Its energy needs are compounded because even some of its newest heavy industry plants do not operate as efficiently, or control pollution as effectively, as factories in other parts of the world, a recent World Bank report said.

Chinese steel makers, on average, use one-fifth more energy per ton than the international average. Cement manufacturers need 45 percent more power, and ethylene producers need 70 percent more than producers elsewhere, the World Bank says.

China's aluminum industry alone consumes as much energy as the country's commercial sector — all the hotels, restaurants, banks and shopping malls combined, Rosen and Houser reported.

Moreover, the boom is not limited to heavy industry. Each year for the past few years, China has built about 7.5 billion square feet of commercial and residential space, more than the combined floor space of all the malls and strip malls in the United States, according to data collected by the United States Energy Information Administration.

Chinese buildings rarely have thermal insulation. They require, on average, twice as much energy to heat and cool as those in similar climates in the United States and Europe, according to the World Bank. The vast majority of new buildings — 95 percent, the bank says — do not meet China's own codes for energy efficiency.

All these new buildings require China to build power plants, which it has been doing prodigiously. In 2005 alone, China added 66 gigawatts of electricity to its power grid, about as much power as Britain generates in a year. Last year, it added an additional 102 gigawatts, as much as France.

This increase has come almost entirely from small- and medium-size coal-fired power plants that were built quickly and inexpensively. Only a few of them use modern, combined-cycle turbines, which increase efficiency, said Noureddine Berrah, an energy expert at the World Bank. He said Beijing had so far declined to use the most advanced type of combined-cycle turbines despite having completed a successful pilot project nearly a decade ago.

While over the long term, combined-cycle plants save money and reduce pollution, Berrah said, they cost more and take longer to build. For that reason, he said, central and provincial government officials prefer older technology.

"China is making decisions today that will affect its energy use for the next 30 or 40 years," he said. "Unfortunately, in some parts of the government the thinking is much more shortsighted."

The Politics of Pollution

Since Hu Jintao became the Communist Party chief in 2002 and Wen Jiabao became prime minister the next spring, China's leadership has struck consistent themes. The economy must grow at a more sustainable, less bubbly pace. Environmental abuse has reached intolerable levels. Officials who ignore these principles will be called to account.

Five years later, it seems clear that these senior leaders are either too timid to enforce their orders, or the fast-growth political culture they preside over is too entrenched to heed them.

In the second quarter of this year, the economy expanded at a neck-snapping pace of 11.9 percent, its fastest in a decade. State-driven investment projects, state-backed heavy industry and a thriving export sector led the way. China burned 18 percent more coal than it did the year before.

China's authoritarian system has repeatedly proved its ability to suppress political threats to Communist Party rule. But its failure to realize its avowed goals of balancing economic growth and environmental protection is a sign that the country's environmental problems are at least partly systemic, many experts and some government officials say. China cannot go green, in other words, without political change.

In their efforts to free China of its socialist shackles in the 1980s and early 90s, Deng and his supporters gave lower-level officials the leeway, and the obligation, to increase economic growth.

Local party bosses gained broad powers over state bank lending, taxes, regulation and land use. In return, the party leadership graded them, first and foremost, on how much they expanded the economy in their domains.

To judge by its original goals — stimulating the economy, creating jobs and keeping the Communist Party in power — the system Deng put in place has few equals. But his approach eroded Beijing's ability to fine-tune the economy. Today, a culture of collusion between government and business has made all but the most pro-growth government policies hard to enforce.

"The main reason behind the continued deterioration of the environment is a mistaken view of what counts as political achievement," said Pan Yue, the deputy minister of the State Environmental Protection Administration. "The crazy expansion of high-polluting, high-energy industries has spawned special interests. Protected by local governments, some businesses treat the natural resources that belong to all the people as their own private property."

Hu has tried to change the system. In an internal address in 2004, he endorsed "comprehensive environmental and economic accounting" — otherwise known as "Green GDP" He said the "pioneering endeavor" would produce a new performance test for government and party officials that better reflected the leadership's environmental priorities.

The Green GDP team sought to calculate the yearly damage to the environment and human health in each province. Their first report, released last year, estimated that pollution in 2004 cost just over 3 percent of the gross domestic product, meaning that the pollution-adjusted growth rate that year would drop to about 7 percent from 10 percent. Officials said at the time that their formula used low estimates of environmental damage to health and did not assess the impact on China's ecology. They would produce a more decisive formula, they said, the next year.

That did not happen. Hu's plan died amid intense squabbling, people involved in the effort said. The Green GDP group's second report, originally scheduled for release in March, never materialized.

The official explanation was that the science behind the green index was immature. Wang Jinnan, the leading academic researcher on the Green GDP team, said provincial leaders killed the project. "Officials do not like to be lined up and told how they are not meeting the leadership's goals," he said. "They found it difficult to accept this."

Conflicting Pressures

Despite the demise of Green GDP, party leaders insist that they intend to restrain runaway energy use and emissions. The government last year mandated that the country use 20 percent less energy to achieve the same level of economic activity in 2010 compared with 2005. It also required that total emissions of mercury, sulfur dioxide and other pollutants decline by 10 percent in the same period.

The program is a domestic imperative. But it has also become China's main response to growing international pressure to combat global warming. Chinese leaders reject mandatory emissions caps, but they claim that the energy efficiency plan will slow growth in carbon dioxide emissions.

Even with the heavy pressure, though, the efficiency goals have been hard to achieve. In the first full year since the targets were set, emissions increased. Energy use for every dollar of economic output fell but by much less than the 4 percent interim goal.

In a public relations sense, the party's commitment to conservation seems steadfast. Hu shunned his usual coat and tie at a meeting of the Central Committee this summer. State news media said the temperature in the Great Hall of the People was set at a balmy 79 degrees Fahrenheit to save energy, and officials have encouraged others to set thermostats at the same level.

By other measures, though, the leadership has moved slowly to address environmental and energy concerns.

The government rarely uses market-oriented incentives to reduce pollution. Officials have rejected proposals to introduce surcharges on electricity and coal to reflect the true cost to the environment. The state still controls the price of fuel oil, including gasoline, subsidizing the cost of driving.

Energy and environmental officials have little influence in the bureaucracy. The environmental agency still has only about 200 full-time employees, compared with 18,000 at the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States.

China has no Energy Ministry. The Energy Bureau of the National Development and Reform Commission, the country's central planning agency, has 100 full-time staff members. The Energy Department of the United States has 110,000 employees.

China does have an army of amateur regulators. Environmentalists expose pollution and press local government officials to enforce environmental laws. But private individuals and nongovernment organizations cannot cross the line between advocacy and political agitation without risking arrest.

At least two leading environmental organizers have been prosecuted in recent weeks, and several others have received sharp warnings to tone down their criticism of local officials. One reason the authorities have cited: the need for social stability before the 2008 Olympics, once viewed as an opportunity for China to improve the environment.

in the town have multiplied from 30,000 in 1986 to nearly 600,000 last year, and the pressure is mounting.

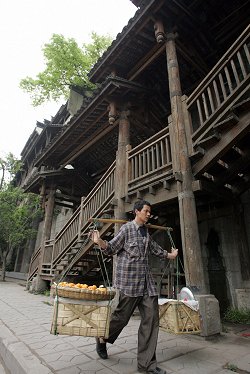

Just 15 years ago Yangshuo was a small village, generally visited for a few hours by those on tours down the Li River; most Chinese tourists elected to take advantage of Guilin's superior accommodation options. After some favorable reports by adventurous overseas guests and glowing write-ups in the ubiquitous Lonely Planet series, Yangshuo gradually became known on Asia's backpacker circuit, offering cheap hostels and banana pancakes to laowai (foreigners) on a budget.

Thanks to China's burgeoning domestic travel sector, Yangshuo started to attract Chinese vacationers in a big way about five years ago, and the town's mix of tourists rapidly changed from nearly 100% foreign to more than 80% native Chinese. Annual increases in tourism in excess of 20% drove the rapid proliferation of hotels and guesthouses as tour operators raced to provide entertainment options for the growing masses.

Commenting on Yangshuo's whirlwind development, Jasmine Yang, owner of a small guesthouse off West Street for the past 15 years, said, "The changes have been amazing. I used to have a lot of foreigners staying here, but now it's mainly tour groups. I had to take out all the dormitory beds because the Chinese don't

in the town have multiplied from 30,000 in 1986 to nearly 600,000 last year, and the pressure is mounting.

Just 15 years ago Yangshuo was a small village, generally visited for a few hours by those on tours down the Li River; most Chinese tourists elected to take advantage of Guilin's superior accommodation options. After some favorable reports by adventurous overseas guests and glowing write-ups in the ubiquitous Lonely Planet series, Yangshuo gradually became known on Asia's backpacker circuit, offering cheap hostels and banana pancakes to laowai (foreigners) on a budget.

Thanks to China's burgeoning domestic travel sector, Yangshuo started to attract Chinese vacationers in a big way about five years ago, and the town's mix of tourists rapidly changed from nearly 100% foreign to more than 80% native Chinese. Annual increases in tourism in excess of 20% drove the rapid proliferation of hotels and guesthouses as tour operators raced to provide entertainment options for the growing masses.

Commenting on Yangshuo's whirlwind development, Jasmine Yang, owner of a small guesthouse off West Street for the past 15 years, said, "The changes have been amazing. I used to have a lot of foreigners staying here, but now it's mainly tour groups. I had to take out all the dormitory beds because the Chinese don't  like the traditional backpacker style of accommodation. I'm making more money, but it's certainly a lot more work."

Whether cruising on the Li River, bamboo rafting on the Yulong River or watching Jiang Yimou's waterborne sound-and-light spectacular Third Sister Liu, water is central to Yangshuo's tourist experience. Unfortunately, and quite predictably, tourism, agriculture and industry are now taking their toll on both the cleanliness and flow of the town's nearby waterways.

While some efforts have been made to remove sources of contamination, "pollution events" often contaminate the Li and Yulong rivers, and in some areas, once-clear water has become murky and algae-ridden. Restaurants, hotels and newly developed scenic spots draw fresh water from the river, dumping trash and untreated sewage back into it in exchange.

Another serious problem is dropping water levels. As scores of ferryboats slowly ply the Li River, beaching on the stony bed is now an increasing phenomenon. Thanks to the increasingly shallow water, navigable stretches may be shortened to as little as 6 kilometers in the dry season. Many Yangshuo residents are concerned that soon the river will disappear entirely.

Liu Gang, a cormorant-fisherman on the Li River, has watched the slow degradation of the source of his livelihood over the past 15 years. "This river used to be full of big fish," he said. "The current

like the traditional backpacker style of accommodation. I'm making more money, but it's certainly a lot more work."

Whether cruising on the Li River, bamboo rafting on the Yulong River or watching Jiang Yimou's waterborne sound-and-light spectacular Third Sister Liu, water is central to Yangshuo's tourist experience. Unfortunately, and quite predictably, tourism, agriculture and industry are now taking their toll on both the cleanliness and flow of the town's nearby waterways.

While some efforts have been made to remove sources of contamination, "pollution events" often contaminate the Li and Yulong rivers, and in some areas, once-clear water has become murky and algae-ridden. Restaurants, hotels and newly developed scenic spots draw fresh water from the river, dumping trash and untreated sewage back into it in exchange.

Another serious problem is dropping water levels. As scores of ferryboats slowly ply the Li River, beaching on the stony bed is now an increasing phenomenon. Thanks to the increasingly shallow water, navigable stretches may be shortened to as little as 6 kilometers in the dry season. Many Yangshuo residents are concerned that soon the river will disappear entirely.

Liu Gang, a cormorant-fisherman on the Li River, has watched the slow degradation of the source of his livelihood over the past 15 years. "This river used to be full of big fish," he said. "The current  would be strong, even in the dry season. In some places the water is really shallow now, and the fish are a lot smaller. Sometimes I don't catch anything worth selling for a few days."

The effect of tourism on the Li River is also a potential threat to the environment along the Yulong River. There is continuing competition between the two scenic areas; Li River tourism is mainly organized by travel agencies as part of packages out of Guilin, whereas Yulong River tourism is run by operators in Yangshuo.

Recruiting, handling and charging as many tourists as possible is now the philosophy of the day for both sets of operators. Anyone hoping for a tranquil cycle ride through the Yulong River rice paddies is likely to be confronted by a succession of buses, noisily navigating the narrow country lanes to transport tour groups to and from their bamboo rafts.

The growth of tourism has brought mixed blessings to the residents of Yangshuo and the surrounding area, and many locals are satisfied with the extra income that the rising influx of tourist dollars and yuan has brought. Some small villages, such as Xing Ping, have river access, and this has resulted in vastly increased revenues for local inhabitants with entrepreneurial flair.

However, despite the financial incentives, many locals are concerned that new development is harming the esthetics of Yangshuo, renowned for its "scenery in the town, town in the scenery" setting. Much of the new construction jars with traditional architecture, and has blemished some previously stunning mountain backdrops.

American tourist Paul Murray is one of many people disappointed on their return to Yangshuo. "I came here four years ago, and despite the obvious sprawl of the town, there was still a feeling that every street was enclosed by an almost magical landscape. It looks like things have got a bit out of control now - there's construction everywhere and nothing looks to be sacred anymore," he commented.

Although sightseeing has long dominated China's domestic market, recreation is growing as a new tourism product. With a booming economy driving up living standards, more and more Chinese are seeking better quality of life, especially those from urban centers. Growing flexibility in how vacations are taken allows domestic tourists time to visit new areas like Yangshuo, and to spend time pursuing a variety of recreational pursuits.

A rapidly improving transport infrastructure is helping these Chinese tourists reach their holiday destinations. A new expressway from Guilin to Wuzhou will soon complete the high-speed road connection from Yangshuo to the cities of the Pearl River Delta, meaning a much-reduced four-hour trip from Guangzhou to Yangshuo, and only an hour or two more from Hong Kong and Shenzhen.

As a nation and a people, the Chinese are now facing a difficult yet vital question: how to achieve growth without causing further environmental degradation. Protecting China's natural beauty now seems to be more of a priority, even if it's just to satisfy requirements for next year's Summer Olympic Games.

However, by fueling a new market for tourism, Beijing must realize that it is piling up the pressure on a number of delicate ecosystems around the country.

The Yangshuo area is a destination with exceptional topography and immense potential for tourism development. At the same time, the area is fragile, and there is a dire need for more integrated planning and management to ensure that development is sustainable, not detrimental, and that tourist-driven revenue benefits all, rather than just a few.

Guangxi is one of the provinces and autonomous regions eligible for support under China's "Go West" project, designed to support development in western and southwestern China. National funding is focusing on key areas, and Yangshuo qualifies for a percentage of the multimillion-yuan package. For the sake of Chinese tourists, backpackers and locals alike, let's hope a sizable amount of this aid is plowed into sustainable tourism.

Daniel Allen is a freelance writer and photographer from London who has lived in China for the past three years.

would be strong, even in the dry season. In some places the water is really shallow now, and the fish are a lot smaller. Sometimes I don't catch anything worth selling for a few days."

The effect of tourism on the Li River is also a potential threat to the environment along the Yulong River. There is continuing competition between the two scenic areas; Li River tourism is mainly organized by travel agencies as part of packages out of Guilin, whereas Yulong River tourism is run by operators in Yangshuo.

Recruiting, handling and charging as many tourists as possible is now the philosophy of the day for both sets of operators. Anyone hoping for a tranquil cycle ride through the Yulong River rice paddies is likely to be confronted by a succession of buses, noisily navigating the narrow country lanes to transport tour groups to and from their bamboo rafts.

The growth of tourism has brought mixed blessings to the residents of Yangshuo and the surrounding area, and many locals are satisfied with the extra income that the rising influx of tourist dollars and yuan has brought. Some small villages, such as Xing Ping, have river access, and this has resulted in vastly increased revenues for local inhabitants with entrepreneurial flair.

However, despite the financial incentives, many locals are concerned that new development is harming the esthetics of Yangshuo, renowned for its "scenery in the town, town in the scenery" setting. Much of the new construction jars with traditional architecture, and has blemished some previously stunning mountain backdrops.

American tourist Paul Murray is one of many people disappointed on their return to Yangshuo. "I came here four years ago, and despite the obvious sprawl of the town, there was still a feeling that every street was enclosed by an almost magical landscape. It looks like things have got a bit out of control now - there's construction everywhere and nothing looks to be sacred anymore," he commented.

Although sightseeing has long dominated China's domestic market, recreation is growing as a new tourism product. With a booming economy driving up living standards, more and more Chinese are seeking better quality of life, especially those from urban centers. Growing flexibility in how vacations are taken allows domestic tourists time to visit new areas like Yangshuo, and to spend time pursuing a variety of recreational pursuits.

A rapidly improving transport infrastructure is helping these Chinese tourists reach their holiday destinations. A new expressway from Guilin to Wuzhou will soon complete the high-speed road connection from Yangshuo to the cities of the Pearl River Delta, meaning a much-reduced four-hour trip from Guangzhou to Yangshuo, and only an hour or two more from Hong Kong and Shenzhen.

As a nation and a people, the Chinese are now facing a difficult yet vital question: how to achieve growth without causing further environmental degradation. Protecting China's natural beauty now seems to be more of a priority, even if it's just to satisfy requirements for next year's Summer Olympic Games.

However, by fueling a new market for tourism, Beijing must realize that it is piling up the pressure on a number of delicate ecosystems around the country.

The Yangshuo area is a destination with exceptional topography and immense potential for tourism development. At the same time, the area is fragile, and there is a dire need for more integrated planning and management to ensure that development is sustainable, not detrimental, and that tourist-driven revenue benefits all, rather than just a few.

Guangxi is one of the provinces and autonomous regions eligible for support under China's "Go West" project, designed to support development in western and southwestern China. National funding is focusing on key areas, and Yangshuo qualifies for a percentage of the multimillion-yuan package. For the sake of Chinese tourists, backpackers and locals alike, let's hope a sizable amount of this aid is plowed into sustainable tourism.

Daniel Allen is a freelance writer and photographer from London who has lived in China for the past three years.